Our e-mail conversation was short yet eye-opening. It actually lasted for a few weeks, with incremental responses only exchanged every couple of days. But only this week I figured out that both, my colleague and I, were engaged in entirely different conversations. The topic was simple – a video that I needed to turn into an internal e-learning. My colleague declined the request advising me that this “format” wasn’t suitable for an e-learning. I assumed the term “format” to refer to the technical aspects of the video, so the actual file type and how it integrated with our learning management system. Turns out that the colleague’s use of “format” actually referred to the content and style of the video (so everything BUT the file format). But as these conversations go, both of us were getting more frustrated with every email added to the conversation. Both of us were convinced to be right and it needed a third person to resolve it. What was behind that? Egocentrism and the curse of knowledge, a cognitive bias that occurs when an individual, communicating with other individuals, unknowingly assumes that others have the background to understand. In light of that, George Bernard Shaw was certainly right in his observation that:

“The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”

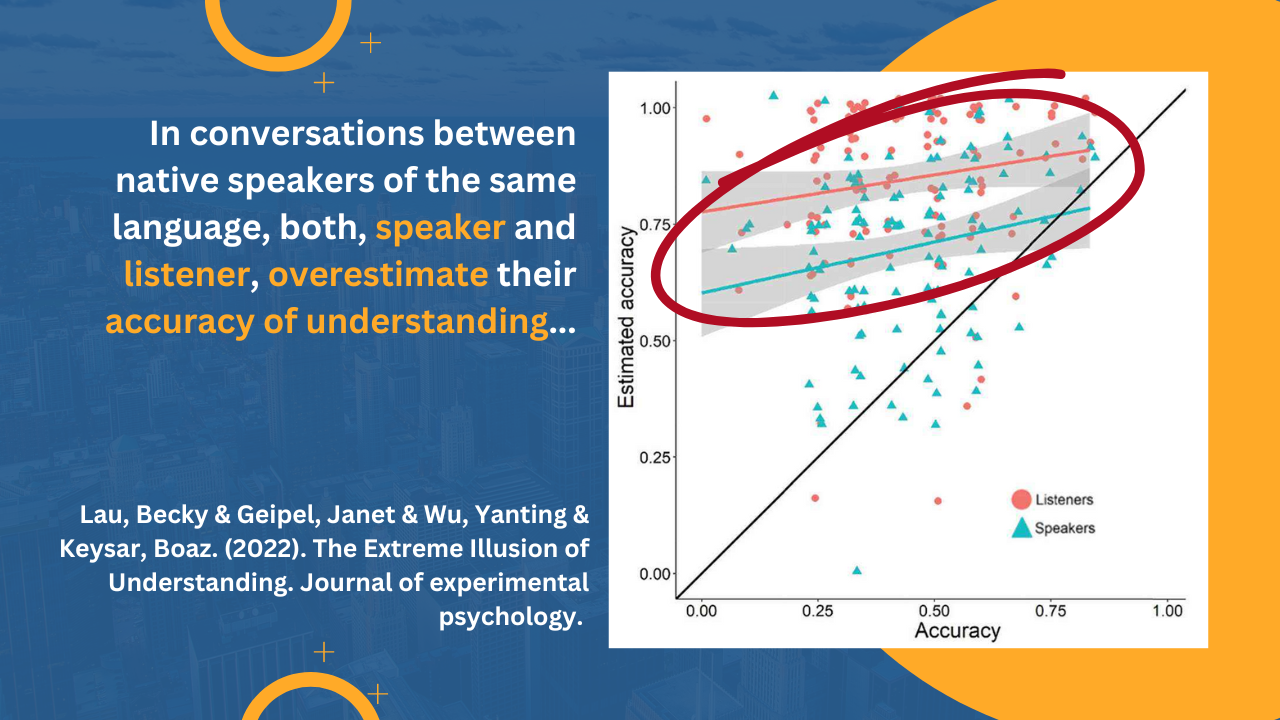

I needed to think of the above experience when reading a study by the University of Chicago (Becky Ka Ying Lau, Janet Geipel, Yanting Wu, and Boaz Keysar) published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology recently. The study investigates the extent to which people overestimate the success of a conversation and their own positive contribution to it – or, as the authors call it, the “illusion of understanding”. In an experiment with native Chinese and English speakers, they used general phrases with four different but commonly known meanings to then double-check the assumed level of understanding and the actual accuracy of understanding. The study’s findings are significant and straightforward (and indeed very disillusioning). Among two native speakers of the same language, the intended meaning was identified correctly in 44% of the cases (which is larger than “by chance” at 25%). But in fact, participants were sure to have correctly identified the intended meaning 85% of the time, resulting in a 41% “overestimation” of communication success. This illusion of communication was also found in the communication between native speakers of different languages. The confidence to have understood the meaning correctly was of course a bit lower at 65%, but the actual accuracy was as well at 35%, resulting in an “overestimation” of communication success of 30%. In a nutshell, in pretty much half of all cases participants were sure to have correctly interpreted the other’s message but were actually wrong: half of all “successful conversations” had indeed failed.

Of course, it makes sense to distinguish different contexts and situations. The authors highlight the validity of their findings for forms of non-interactive communication such as emails, letters, and chats. And that relates back to my own experience from last week. Using phrases or words with double meanings in writing bears a significant risk of misunderstanding the intended message. If we had discussed the topic in a meeting or call, the same misunderstanding would probably not have happened. The added context would have enabled each of us to better understand the other’s intended messages.

This is a copy of the same post on my LinkedIn blog. To comment and join the discussion on this topic switch to LinkedIn. Follow me for regular updates and blog articles: https://www.linkedin.com/in/drnilskoenig/